Poznański Czerwiec 1956 was the first major workers’ uprising in post-war Poland, exposing the deep fractures within the Polish People’s Republic (PRL). Sparked by economic hardship and political dissatisfaction, the protests in Poznań marked a pivotal moment in the struggle for workers’ rights and social justice. The brutal suppression of the uprising revealed the state’s willingness to use violence against its own citizens, while the events laid the foundation for future resistance movements across Poland.

The Socio-Economic Context

By the mid-1950s, Poland was experiencing severe economic strain. The centrally planned economy, a hallmark of the Soviet model, led to widespread inefficiency and stagnation. Industrial workers faced increasing workloads without corresponding wage increases, while food shortages and rising prices exacerbated public frustration.

Poznań, as one of the nation’s largest industrial hubs, bore the brunt of these economic difficulties. The city’s Zakłady Cegielskiego (Cegielski Works), a flagship enterprise employing thousands, became a focal point of worker discontent. Employees at the plant were subject to unrealistic production targets, wage cuts, and worsening living conditions. Promised bonuses were withheld, and bureaucratic inefficiency fuelled resentment.

In the years leading up to 1956, murmurs of dissatisfaction grew louder. The deaths of Soviet leaders Joseph Stalin in 1953 and Bolesław Bierut, Poland’s hardline communist leader, in 1956 created a political atmosphere ripe for change. However, the new leadership under Edward Ochab continued to enforce harsh policies, failing to address workers’ grievances.

The Outbreak of Protests

On 28 June 1956, discontent boiled over. Workers at Cegielski Works, driven by economic desperation, walked off the job and marched through the streets of Poznań. The march began peacefully, with workers demanding better wages, improved working conditions, and the fulfilment of state promises. Their slogans, such as „Chcemy chleba” (We want bread) and „Precz z komuną” (Down with communism), encapsulated the growing frustration with the system.

The demonstration quickly grew in size, drawing thousands of participants from factories and local communities. By mid-morning, the marchers converged at Plac Stalina (now Plac Adama Mickiewicza), transforming the square into the heart of the protest. Initially, city officials and the local police appeared overwhelmed but refrained from intervening directly.

However, as the demonstration escalated, some protesters stormed key government buildings, including the local party headquarters, court buildings, and police stations. The demonstrators freed political prisoners and seized weapons from an armoury, further intensifying the confrontation. By midday, Poznań was in a state of chaos, with government authority severely weakened.

Military Intervention and the Bloody Crackdown

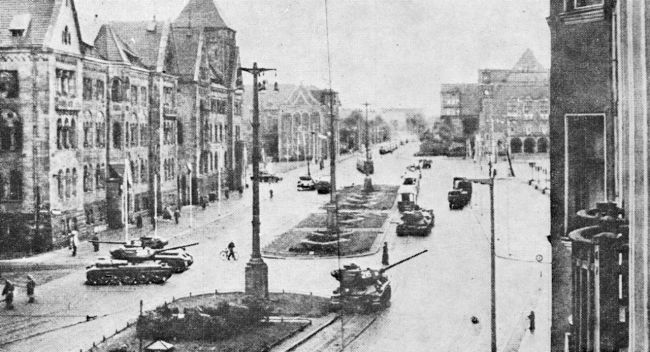

Faced with an escalating crisis, the government in Warsaw ordered the deployment of military units to restore control. Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz and Defence Minister Konstanty Rokossowski, a Soviet marshal, spearheaded the operation. By the afternoon of 28 June, tanks, armoured vehicles, and soldiers entered Poznań, initiating a brutal crackdown.

The most violent clashes occurred near the police headquarters and Plac Stalina. Soldiers opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, and bystanders were caught in the crossfire. One of the most enduring and tragic symbols of the crackdown was the death of Romek Strzałkowski, a 13-year-old boy who became one of the youngest victims. His death galvanised public outrage and became emblematic of the uprising’s human cost.

The violence continued throughout the night and into the next day. By the time order was restored, at least 58 people had been killed, with unofficial estimates placing the death toll even higher. Over 600 others were wounded, and hundreds more were arrested. Despite the bloodshed, the state framed the uprising as the work of „imperialist agents” attempting to destabilise the country, downplaying the role of workers and civilians.

Political Fallout and Leadership Changes

The Poznań protests rattled the upper echelons of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). While the official narrative sought to attribute the unrest to external provocateurs, the leadership recognised the need for internal reform to prevent further uprisings.

In the months following the protests, Edward Ochab was replaced by Władysław Gomułka, a former party leader who had been sidelined during the Stalinist era. Gomułka’s return to power was widely perceived as a concession to public pressure. In October 1956, during a speech to workers in Warsaw, Gomułka acknowledged the grievances that had led to the June uprising, promising to implement economic reforms and reduce the influence of Soviet advisors in Poland.

Though Gomułka’s leadership brought a brief period of liberalisation, the fundamental structures of communist rule remained unchanged. His promises of greater autonomy and political freedom ultimately proved limited, but the memory of Poznański Czerwiec lingered as a symbol of defiance.

The Role of Workers and the Broader Impact

The Poznań uprising marked the first mass-scale expression of workers’ dissent in the Eastern Bloc, preceding similar movements in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. It underscored the deep rifts between the state and the populace, demonstrating the limits of authoritarian control over an increasingly frustrated working class.

For many participants, the uprising represented a turning point. Poznań’s workers, who had initially sought economic justice, inadvertently became pioneers of a broader movement for political change. Their willingness to confront the state emboldened subsequent generations of activists and trade unionists, culminating in the rise of Solidarność (Solidarity) in the 1980s.

The symbolic importance of Poznański Czerwiec also influenced the Polish Catholic Church, which offered moral and spiritual support to the victims’ families. This alignment between the Church and workers’ movements strengthened over the following decades, playing a crucial role in shaping Poland’s opposition to communist rule.

Commemoration and Historical Memory

In the years after the uprising, the Polish state attempted to suppress public discussion of Poznański Czerwiec. Official memorials were sparse, and the government-controlled press provided minimal coverage of the events. However, the memory persisted, passed down through families and local communities.

In 1981, on the 25th anniversary of the uprising, the Monument to the Victims of June 1956 was unveiled at Plac Adama Mickiewicza. The monument, depicting a pair of massive crosses, stands as a tribute to the demonstrators who lost their lives in the fight for bread and freedom. The inscription „Za wolność, prawo i chleb” (For freedom, rights, and bread) reflects the demands that fuelled the uprising.

Today, Poznański Czerwiec is commemorated annually, serving as a reminder of the sacrifices made by workers in the pursuit of justice. The uprising stands as a testament to the enduring strength of Polish civil society and its role in shaping the nation’s path toward democracy and self-determination.