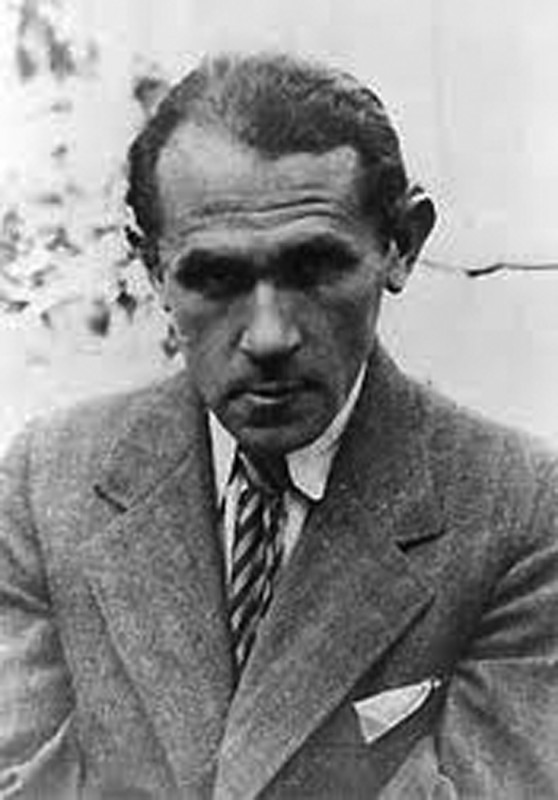

Bruno Schulz, one of Poland’s most distinctive literary figures, left behind a small but profoundly influential body of work that continues to captivate readers worldwide. His dreamlike prose, rich with symbolism and myth, draws on personal memory, Jewish heritage, and the surreal landscapes of his hometown, Drohobych. Schulz’s writing, though sparse in quantity, stands as a cornerstone of Polish modernist literature.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

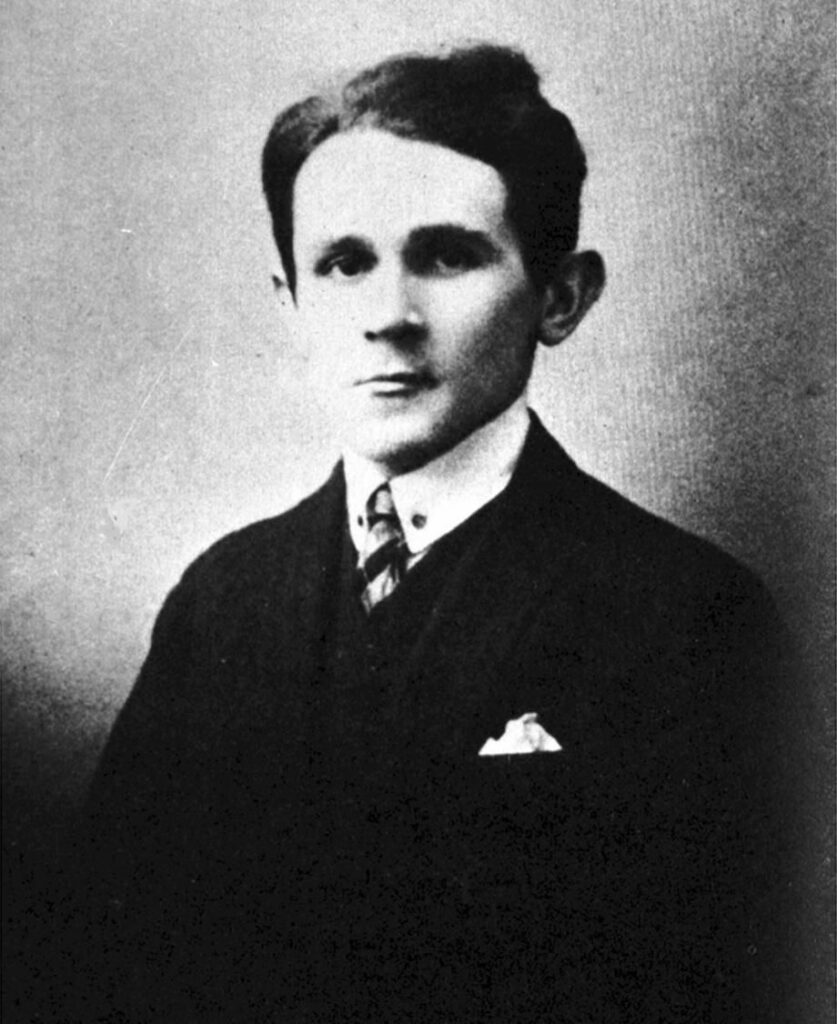

Bruno Schulz was born on 12 July 1892 in Drohobych, a small Galician town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now in Ukraine). The atmosphere of this provincial town—marked by its diverse population of Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews—would later shape the fantastical, layered settings of his fiction. Schulz belonged to a middle-class Jewish family; his father, Jakub, owned a textile shop, while his mother, Henrietta, managed the household.

Schulz’s early life was steeped in art and literature. After completing his schooling in Drohobych, he enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture at the Lviv Polytechnic. However, his true passion lay in drawing and painting, and he shifted his focus to art. Schulz’s visual artistry, characterised by intricate, fantastical sketches, often served as a precursor to his literary endeavours.

Returning to Drohobych, Schulz took up a position as a drawing teacher at the local gymnasium, a role he would hold for most of his life. Though his teaching career provided stability, it was his nocturnal artistic pursuits—drawing, painting, and writing—that defined his identity.

Literary Breakthrough – „The Street of Crocodiles”

Schulz’s literary debut came in 1934 with the publication of Sklepy cynamonowe (The Street of Crocodiles). The collection of short stories, loosely connected by recurring characters and motifs, transports readers into a surreal, mythical vision of Drohobych. The narrative, fragmented and dreamlike, blurs the boundaries between reality and fantasy, creating a universe where the mundane transforms into the extraordinary.

At the heart of The Street of Crocodiles is the figure of the Father, a semi-autobiographical portrayal of Schulz’s own father. This eccentric, godlike character exudes both fragility and mystical power, serving as a conduit between the tangible world and the realm of imagination. Through elaborate metaphors and rich sensory descriptions, Schulz weaves a tapestry of memories, familial tensions, and the lingering melancholy of a vanishing world.

Critics lauded Schulz’s originality, likening his prose to that of Franz Kafka. Indeed, Schulz’s dense, metaphorical style and focus on individual alienation echo the existential undercurrents of Kafka’s work. Yet, Schulz’s voice remained uniquely his own—rooted in the specificity of Jewish-Polish provincial life and filtered through a prism of myth and personal memory.

„Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass”

In 1937, Schulz published his second and final collection, Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą (Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass). Like The Street of Crocodiles, this work draws on childhood memories and the haunting spectre of his father’s declining health. The stories are more introspective and labyrinthine, delving deeper into the nature of time, mortality, and the blurred lines between life and death.

In Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, the narrator navigates a fantastical sanatorium where time itself bends and warps. The narrative, marked by Schulz’s signature ornate style, unfolds in a series of fragmented episodes that explore the impermanence of existence and the malleability of memory.

Though Schulz’s literary output was modest, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass solidified his reputation as one of Poland’s leading modernist voices. His prose, steeped in rich allegory and philosophical depth, challenged the conventions of linear storytelling, aligning him with the avant-garde currents sweeping through European literature.

A Life in the Shadows of War

As war loomed over Europe, Schulz’s position as a Jewish intellectual in Poland grew increasingly precarious. When Nazi forces occupied Drohobych in 1941, Schulz was confined to the town’s ghetto. Despite the dangers, he continued to write and sketch, though much of his wartime work has been lost.

During this time, Schulz fell under the protection of Felix Landau, a Gestapo officer and art enthusiast who commissioned him to paint murals in his home. Schulz’s status as Landau’s “pet Jew” offered temporary reprieve from deportation, but it also marked him for retribution. On 19 November 1942, Schulz was shot and killed by Karl Günther, another Gestapo officer, in an act of personal vendetta against Landau.

Schulz’s death, at the age of 50, robbed the literary world of one of its most enigmatic voices. His untimely end, coupled with the loss of much of his unpublished work, cemented his status as a tragic figure in Polish and Jewish cultural history.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Despite his brief career, Schulz’s influence on Polish literature remains profound. His works, once overshadowed by the tumult of World War II and post-war censorship, were rediscovered in the 1950s and 60s, spurring renewed interest in his surreal, myth-infused narratives. Today, The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass are regarded as masterpieces of modernist literature, translated into numerous languages and adapted for theatre, film, and visual art.

In 2001, fragments of Schulz’s lost murals were rediscovered in the former Landau villa, reigniting global interest in his visual art. Though the murals were controversially removed and relocated to Israel’s Yad Vashem, they stand as a testament to Schulz’s enduring legacy as both a writer and an artist.

Schulz’s life and work continue to inspire scholars, artists, and readers, ensuring his place within the pantheon of Poland’s literary greats. His visionary storytelling, deeply rooted in personal myth and collective memory, remains a haunting reflection of a world that no longer exists but lives on through his extraordinary prose.