The events of December 1970 (Grudzień 1970) stand as one of the darkest chapters in Polish post-war history. What began as protests against sudden price hikes quickly escalated into a violent confrontation between the authorities and workers along Poland’s northern coast. The brutal suppression of demonstrations in cities like Gdańsk, Gdynia, Elbląg, and Szczecin revealed the harsh nature of the Polish People’s Republic (PRL) and its willingness to use lethal force to maintain control.

The Spark: Economic Crisis and Rising Prices

In December 1970, the Polish government, led by Władysław Gomułka, announced sharp increases in the prices of essential goods, including food. This decision, made without public consultation, came at a time when wages stagnated, and living conditions were already strained. For many Poles, the price hikes—particularly for meat and basic groceries—were unbearable.

The timing of the announcement, just days before Christmas, further inflamed public anger. Workers, who relied on these staples to prepare for the holiday season, felt betrayed and abandoned by the state.

The Outbreak of Protests

The first demonstrations erupted on 14 December 1970 in Gdańsk’s shipyards, one of Poland’s largest industrial centres. Workers staged strikes and marched through the city, demanding the withdrawal of price increases and better economic policies. By the next day, the protests spread to Gdynia, Elbląg, and Szczecin, as workers from shipyards, ports, and factories joined the growing unrest.

Demonstrators chanted slogans against the government, tore down communist banners, and called for reforms. In response, the authorities deployed police and military units, marking the beginning of a violent crackdown.

The Gdynia Massacre – „Janek Wiśniewski Padł”

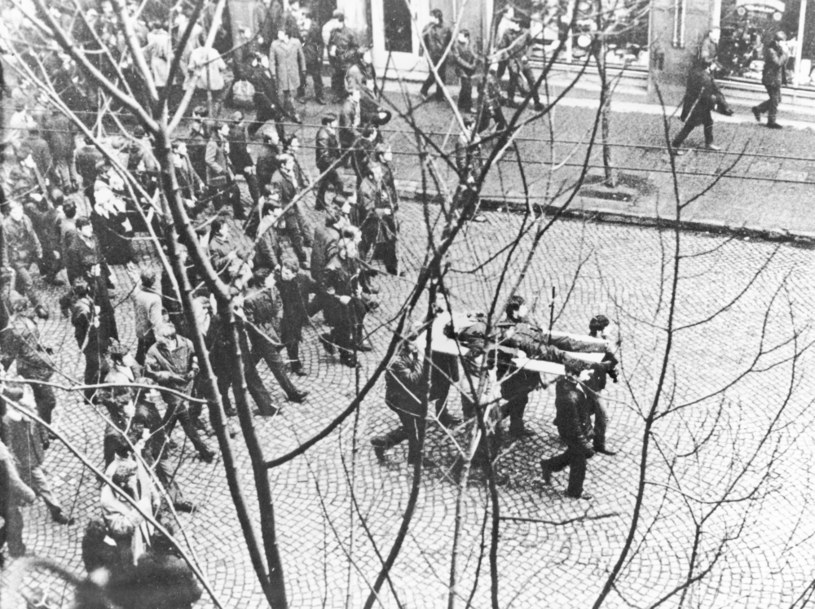

The most tragic incident occurred on 17 December 1970 in Gdynia. As workers arrived at the shipyard in the early hours, they were met by soldiers and tanks. Without warning, the military opened fire on the crowd. Many were killed on the spot, while others were fatally wounded as they attempted to flee.

One of the most enduring symbols of this massacre is the figure of Janek Wiśniewski—a fictional name representing the real victims of that day. The image of a young man’s lifeless body, carried on a wooden door through the streets of Gdynia by fellow workers, became a powerful symbol of the regime’s brutality. This act of defiance and mourning was immortalised in the ballad „Ballada o Janku Wiśniewskim” and later depicted in Andrzej Wajda’s film Człowiek z Żelaza (Man of Iron).

Spread of Unrest and the Government’s Response

The violence in Gdynia ignited further protests across the coastal cities. In Szczecin, demonstrators set fire to government buildings, while in Gdańsk and Elbląg, clashes between workers and security forces continued for several days. Despite the mounting casualties, the protests persisted, reflecting widespread disillusionment with the government.

Fearing the spread of unrest to other parts of Poland, the authorities imposed curfews, deployed the army, and arrested thousands of protesters. By the end of December, at least 45 people had been killed, and over 1,000 were injured.

Political Fallout – The Fall of Gomułka

The massacre of December 1970 marked the beginning of the end for Władysław Gomułka. Although initially hesitant, the Polish Communist Party’s leadership recognised the need for political change to prevent further unrest. On 20 December, Gomułka was forced to resign, and Edward Gierek took over as First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR).

Gierek, seeking to distance himself from the violence, promised economic reforms and greater dialogue with workers. His rise to power was framed as a shift towards a more conciliatory and pragmatic leadership, though the fundamental structures of authoritarian rule remained intact.

A Lasting Legacy

The events of December 1970 left deep scars on Polish society. For many, the massacre underscored the true nature of the PRL—an authoritarian regime willing to shed the blood of its own citizens to preserve power. The coastal cities where the protests took place became symbols of resistance and remembrance.

Annual commemorations honour those who lost their lives, with monuments erected in Gdynia and Gdańsk. The Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970 in Gdańsk, unveiled in 1980, stands as a tribute to the victims and a reminder of the cost of freedom.

The memory of December 1970 also played a critical role in shaping the later protests of 1980, which led to the rise of Solidarność (Solidarity). Many shipyard workers who had witnessed the massacre a decade earlier became leaders in the push for greater political and economic rights.

Reflection on State Violence

Grudzień 1970 serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked state power and the fragility of civil rights under authoritarian regimes. It highlights the resilience of the Polish people and their persistent struggle for justice and dignity.

Though the PRL sought to suppress the memory of these events, the truth endured, passed down through songs, stories, and monuments. Today, the tragedy of December 1970 stands as a testament to the sacrifices made by ordinary workers in the fight for a more just and democratic Poland.